Neighborhood Pattern of Tantibazar, Dhaka : How can a community be developed slowly based on some socio-cultural factors

Tantibazar is such a significant neighborhood that reflects the organic settlement pattern of historic Dhaka with a unique morphological identity of compact and linear buildings with a narrow frontage along a spinal axis. This blog will discuss the neighborhood pattern and its impact on socio-cultural aspects.

COMMUNITYHERITAGE

Mahmuda Yasmin Dola, Muhammad Golam Sami

10/13/20223 min read

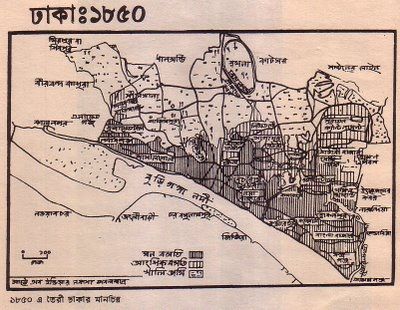

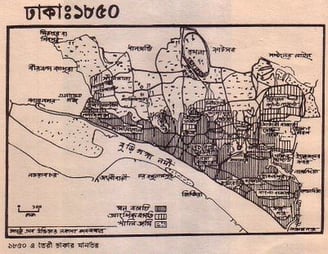

Image: Map of old Dhaka'1850 (BD Archive)

Social relationships and human connection are severe and essential factors in the life and residence of people. However, the consequences of industrial and modern life have recently faded human relationships. Many sociocultural factors can directly or indirectly affect community development, such as attitudes, cross-cultural differences, cultural identity, trade, family structure, religious beliefs, religious practices, education, income level, etc. In addition, morphological development, physical pattern, building fabric, street facade, building-space relationship, and responsiveness are the parameters for the development of a community.

It is believed that the harmonious relationship of these factors makes the settlement sustainable. The spatial pattern of the neighborhoods was sustainable as they grew out of the community's needs. For example, the spatial pattern of a specialized neighborhood (Tantibazar) reflects the character of the traditional settlement pattern of Dhaka to develop it as a cultural heritage and a symbol of sociocultural sustainability. The spatial hierarchy within the neighborhood forms the urban fabric that reflects the indigenous settlement character of Bengal and the rural pattern of life. Again, Tantibazar is also a kind of mohalla. The area is mainly a commercial hub with residential quarters at the back of the shops. These mohallas were considered the morphological archetype of historic Dhaka.

Rapoport (1977), states that a house form is the consequence of a range of sociocultural factors seen in their broadest terms. In its basic form, a traditional rural 'Bengali House' is a cluster of small 'shelters' of huts around a central yard, locally called the uthan. Traditionally, the people of Bengal have a habit of socializing in outdoor spaces. This habit led to the formation of traditional outdoor civic spaces and different human activities, such as Uthan, Galis, MohaIla, Morh, Chawk, Bazar, etc. At the micro-level, the courtyard is the most vibrant place for geo-climatic reasons and social interaction. It is the breathing space for the dwellers. The houses with a courtyard and a mandir create activities for the neighborhood to perform religious rituals that act as a form of urban space. The facade articulation around the courtyard also encourages outdoor activities, thus improving building socialization through the semi-open verandahs.

This form of community relationship is also visible in the area of Tantibazar. The face-to-face relationship of the mohalla residents is another contributing factor to the sense of community. In this settlement, the narrow road plays a significant role in the social relations of the community and works like a magnet for the settlement. The frontage of the series of shops also provides a place for interaction. Another place to gather is the religious structure. So, civic facilities are incorporated at the human scale to develop interactions among the inhabitants.

Organic cities are claimed to reflect the 'community spirit'; the building's character, especially uniformity and continuity, expresses the shreds of evidence of the previous era and symbolizes unity in the neighborhood's social life. Above all, these will promote one step towards sustainable community development. So, this is what we discussed above: a community can be developed slowly based on some sociocultural factors.

An overall observation of Tantibazar from literature:

Tantibazar is a significant neighborhood that reflects the organic settlement pattern of historic Dhaka. Its unique morphological identity consists of compact, linear buildings with narrow frontage along a spinal axis. The linear mahalla represents a strong sense of neighborly relation due to the same occupation, ethnicity, and caste, creating social cohesiveness within the members.

At an intimate scale, the bazaar street works as a community place. The face-to-face relationship among the streetscape makes the street vibrant and acts as a catalyst to increase social bondage.

The Galis (Lane) makes the street level more vibrant with overlapping activities such as communication and social gatherings. It also makes the neighborhood environment-friendly.

Courtyard house pattern is geo-climatically and socio-culturally efficient for this region's living pattern and contextual base.

The hierarchy of spaces from the public domain to the private domain creates a sequence of socialization spaces and a sense of control, which is sustainable in this region, where it provides seclusion to women from male visitors.

The enormous number of voids in the built form helps to interact with urban spaces. Elements like courtyards, verandahs, and windows enhance the indoor-outdoor relationship.

Source: Tabassum, T. (2011). Analyzing a Traditional Neighbourhood Pattern of Old Dhaka: A Case of Tantibazaar.

Meet The Authors

Muhammad Golam Sami

B. Arch, Khulna University of Engineering & Technology, Khulna, Bangladesh Architect | Futurist | Sustainable Design Expert

Operational Head, ADORA Studios, Bangladesh

Founder, samism.org

Lecturer, Department of Architecture

Northern University of Business & Technology

Mahmuda Yasmin Dola

B. Arch, Khulna University of Engineering & Technology, Khulna, Bangladesh Architect | Analytical Practitioner

Head of Construction, ADORA Studios, Bangladesh

CMO & Head of Construction, SS Construction & Power Solution, Bangladesh

Related Articles